Tales of magical dwarves who trade magical assistance for some future object were common enough in 19th century Germany that the Grimm brothers found four separate tales in the Hesse region alone to combine into the tale that they called “Rumpelstiltskin,”—not to mention several other closely related tales. And it wasn’t just Hesse. As the Grimms noted in their extensive footnotes to the tale, nearly every element of Rumpelstiltskin had an analogy somewhere else in European folklore and literature, from songs to the elaborately crafted French salon fairy tales to legends about the life of St. Olaf.

So what made this version stand out—particularly since it wasn’t even the only story about magical spinners in their collection?

“Rumpelstiltskin” starts out by introducing a miller and his lovely daughter. The word “miller” may conjure up thoughts of poverty and peasants, but this particular miller, as it turns out, is not only wealthy enough to buy his daughter a couple of pieces of decent jewelry, but has enough social status to have an audience with the king. Then again, the idea of a miller having an audience with a king is odd enough that the miller, at least, seems to think that he has to explain it: his daughter, the miller says, can spin wheat into gold.

This should immediately raise a number of questions, like, if his daughter actually has this skill, why is he still working as a miller? Does he just find the process of churning wheat into flour all that satisfying? Or, does the local area have so few millers that he can actually make more money from flour than gold? Or, does he believe that just having lots of money isn’t enough: he also has to control the area’s main food supply? Or is he one of those people who just has to mill his own flour to make sure that it meets his very particular requirements? (Don’t laugh; I’ve met someone like that.) Is he perhaps unable to tell the difference between golden straw and metallic gold? At a distance, in the wrong light, that’s maybe an understandable mistake.

Or, well, is he simply lying?

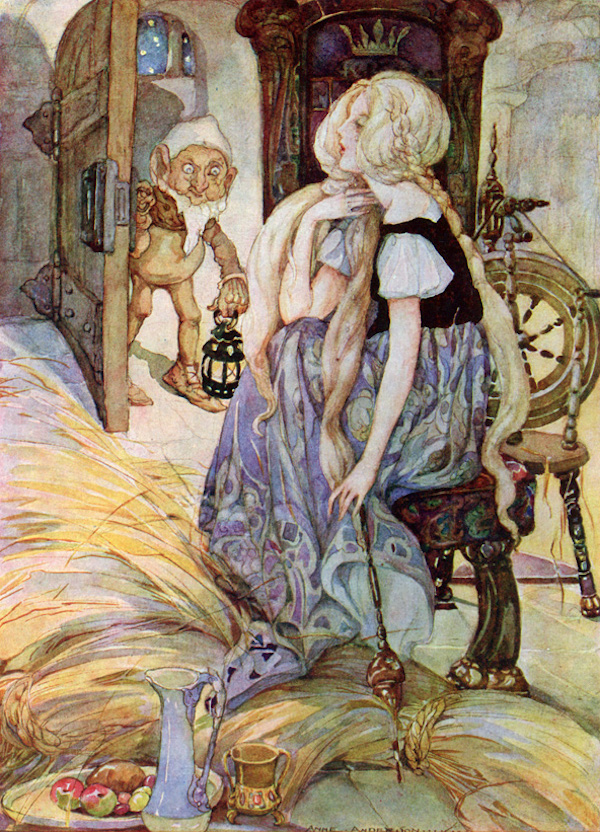

The king, not being the gullible sort, or the sort who reads a lot of fairy tales—take your pick—is inclined to think that yes, the miller is lying. As a test—or perhaps a punishment—the king decides to bring the girl to his castle and lock her into a room with straw, spindle, and spinning wheel. If she can turn that straw into gold, she gets to live. If she can’t, she dies.

This all seems extremely unfair—after all, the girl wasn’t the one to lie to the king. Though I suppose that any king that doesn’t hesitate to punish a daughter for her father’s lies also probably won’t hesitate to come after the miller later. And I suppose it is a punishment for the miller as well.

Unless the miller was just looking for a way to get rid of his daughter. In which case, well played, miller, well played.

Two sentences later, we discover that—surprise!—the miller was in fact lying. One point to the king for figuring this rather obvious point out rather than following my example of asking an endless series of probably unrelated questions. Anyway. We know this, because the girl is crying helplessly, surrounded by straw, and a tiny little man knows this, presumably because he’s been waiting around the castle for an opportunity to trade magic for royal children, and this seems like the perfect opportunity.

Sure, the story doesn’t say he’s just been waiting around the castle all this time—but I find his convenient arrival very suspicious. Consistent with fairy tales, sure, but very suspicious.

In any case, he agrees to spin the straw into gold if she will give him her necklace—a necklace that suggests that the miller is probably doing quite well for himself if it can pay for all that gold and his daughter’s life, although perhaps the girl just felt that she was paying for one night of labor. The pattern is repeated on the second night, with a larger room filled with straw, and the girl’s ring.

After this, the king starts having very romantic thoughts. I quote directly:

“She’s only a miller’s daughter, it’s true,” he thought; “but I couldn’t find a richer wife if I were to search the whole world over.”

On her side, the king is the guy who has threatened to kill her, twice at this point. On the other hand, the king also hasn’t chosen to inquire about the gold spinning all that closely, probably a good thing since technically she isn’t the one doing it (and the story clarifies that she never asks the little man to teach her this rather useful trick).

I mention this in part because it serves as yet another powerful counterpart to the ongoing myth that “fairy tales” must include romances and charming princes and kings and loving princesses, who fall in love. At no point in this tale does anyone fall in love—you’ve just read the most romantic part of it—and although that is probably a better reflection of the realities of many royal marriages, which for centuries were usually arranged for political or financial purposes, not for love, somehow or other, this very realistic look at marriage for money in a fairy tale never manages to squirm into our popular use of the term “fairy tale.”

The girl, meanwhile, has another problem: she’s out of jewelry to trade to the little man for a third batch of transformed straw. He tells her that he’ll accept her first born child when she is Queen instead. The girl, having also not read enough fairy tales (REALLY, FAIRY TALE CHARACTERS, READING THESE STORIES IS IMPORTANT AND COULD SAVE YOUR LIVES AND THE LIVES OF YOUR CHILDREN DON’T NEGLECT THIS IMPORTANT STEP) decides that since she’s out of options and has no idea what might happen before then, she might as well.

This is a good moment to interject that this story was told and took place in a period where women often died in childbirth or shortly thereafter from infection. Just five years after “Rumpelstiltskin” was published, the wealthy, pampered and otherwise healthy Princess Charlotte of Wales would die just a few hours after giving birth to a stillborn son, and she was just the most famous and publicized of deaths in childbed. And that, of course, was only when women could give birth; several women, aristocratic and otherwise, found themselves infertile. The miller’s daughter also has no particular reason to think that this king has any particular love for her as a person—to repeat, he’s threatened her life twice before this—meaning that she’s right on this one part: the odds are in favor of something happening to her before she has to give up her child to a little man with the ability to spin straw into gold.

And thus, she marries the king. Incidentally, he apparently never asks just how she’s able to pull off this trick. Nor does anyone else. I suspect they are all intelligent enough to realize that something magical is involved, and that they’re better off not knowing. And to his (very limited) credit, he does not ask her to spin more straw again. Perhaps he finally has enough gold, or perhaps he’s realized that suddenly releasing all of this gold into the local economy could end up sending inflation spiraling which is perhaps not an economic condition he really wants to deal with. I mean, at least so far, he seems a fairly practical and insightful man, if not exactly a kindly or romantic one. I could see him wanting to avoid an economic crisis.

Anyway. The king’s about to leave the story completely, so let’s stop worrying about his economic issues, and worry about more immediate dangers. One year later, the Queen has her child, and the little man shows up, demanding payment unless she can guess his name. Not surprisingly, the Queen decides to turn to help not to her father, who got her into this mess in the first place, nor to the king, who would presumably agree to turn the kid over for more gold, but to a messenger. Exactly why she feels capable of trusting this guy, given that he can now tell the king and everyone else that the Queen has a weird obsession with names and may just be involved in magic, is not clear, but perhaps she figures that people have already made a few correct guesses, and that really, given her status as a non-princess involved in some highly unusual transformation magic turned Queen and mother of the kingdom’s heir she’s… kinda doomed if she doesn’t do something to save the kid and that she can maybe use that status to do a bit of intimidating.

Or she’s seeing the messenger on the side and the Grimms just decided to edit out that part.

I should also point out, in all fairness, that according to the Grimms in one version of the story the king, not a messenger, found out the little man’s name. Perhaps they felt that the king was too much of a jerk to deserve a nice heroic ending, or perhaps they just figured that the other three versions were more important.

In any case, her gamble works out: three days later, the messenger finds out the man’s name, and the Queen saves her child. The little man kills himself.

The story has been interpreted in many ways—as a tale of parental abuse, as a tale of a woman finally overcoming the three men who have all, in their own way, used her and victimized her, as a warning against deals with the devil, or deals involving some future event, and as a warning against claiming skills and abilities you don’t actually have. Sure, it all mostly works out for the girl in the end, but only after quite a lot of emotional trauma, and then the second shock of thinking that she might lose her son, plus, getting trapped in a loveless marriage. Jane Yolen interpreted this tale as an anti-Semitic one, one featuring a little man with gold, who wants a queen’s child for uncertain, but quite probably dark purposes—details frequently associated with anti-Semitic tales and propaganda.

It also can be, and has been, interpreted as a veiled discussion of the tensions between men and women—not so much because of what is in this tale, but because of its contrast with another tale of spinning and lies collected by the Grimms, “The Three Spinners.” In that tale, the helpers are elderly women, not little men, who help out a decidedly lazy girl who hates to spin. That girl, too, becomes a queen—and no one dies. Partly because she keeps her promise to them—but then again, those women don’t ask her for her first born child. It forms a strong contrast to “Rumpelstiltskin.”

Buy the Book

Finding Baba Yaga: A Short Novel in Verse

It all emphasizes just how much of an oddity both stories are for the Grimms, not so much for their violence and magic—their other tales have plenty of that—but because the Grimms tended to focus on stories that rewarded virtue and hard work. Here, the arguably least virtuous person in the story, the miller, is apparently barely punished for his lie: sure, he has the initial horror of having his daughter snatched away from him, and yes, the story never mentions whether or not he ever sees her again from anything but a distance. On the other hand, nothing happens to him personally, in stark contrast to every other character in the story except arguably the king—and even he ends up with a wife who doesn’t trust him enough to say, uh, hey, we may have a bit of a problem with the heir to the throne here. And the only characters in the story who do any work—the little man and the messenger—never receive any reward for it. Oh, I suppose the miller is also a worker—or at least a member of the working class—but we don’t see him working in the story.

And that might be just where its power comes from. It’s almost refreshing to see a story where diligent research, and the ability to hire a research assistant, brings about the happy ending. Oh, that element is not entirely unknown in fairy tales—the French salon fairy tales, in particular, offer many examples of fairies diligently studying fairy law to find ways of breaking curses, for instance.

But I also think it gains its power from its reassurance that terrible promises and very bad deals can be broken. Not easily, and not without cost. But if you have been forced to make a promise under duress—a situation all too common when this story was told in the 19th century, and not exactly unknown now—this offers hope that perhaps, with cleverness and luck, you might just get out of it. Ok, out of part of it—the girl is still married to the rather greedy king, who never gave a single hint of loving her. But at least she saved her son.

It may be a story of betrayal, of greed, of threats, a fairy tale almost entirely lacking in love—but it does at least offer that hope.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

I didn’t remember the part about Rumple killing himself. Seems like an over-reaction. Perhaps he never realized that attempting to trade babies for favors is far harder and less rewarding than finding a nice woman to marry and settle down with.

@1/AlanBrown: He didn’t intend to kill himself. He got so angry that he stamped his right foot so hard that he drove it into the ground. Since this didn’t make him any less angry, he next grabbed his left foot with both hands (presumably because it was the only thing he could reach) and tore himself into two pieces. I guess you could also read the story as a warning against violent anger.

deleted by author

In some versions he tears himself in half with rage. In some versions he runs off angrily into the night. In at least one of the Grimms’ source versions he flies away on a ladle, presumably to meet up with Baba Yaga on her mortar and pestle and complain about kids these days.

@3/James M Six: Most of the Grimm characters don’t have names, but some do, e.g. Hansel and Gretel.

@4/Sovay: I just checked. He runs away in the first edition and tears himself apart in all subsequent editions.

The King gets a rich wife, and the Miller’s daughter gets to be queen. At this point she probably feels she deserves to be queen after what she’s been through.

The version of the Three Spinners I remember has the trouble start with a mother pretending her idle daughter is a terrific spinster and attracting the attention of the rather good looking son of the local lord who is as pleased by the girl’s supposed industry as he is by her looks. Then he’s introduced to her supernatural help and the deformities of the three spinsners, caused by their spinning, causes the young man to command his fiancee never to spin again – which is just fine by her.

And maybe the horse will learn to sing.

The word “miller” may conjure up thoughts of poverty and peasants, but this particular miller, as it turns out, is not only wealthy enough to buy his daughter a couple of pieces of decent jewelry, but has enough social status to have an audience with the king.

Millers actually tended to be rather upper-middle class and wealthy by the standards of the peasantry. They got to keep a share of everything they ground and usually were appointed to the position by the local nobility who owned the mill. All the peasants subject to that noble had to go to that miller and pay his price. Millers are sometimes good and sometimes bad in fairy tales, though it’s usually the children who are all right.

My favourite modern spin on Rumplestiltskin is Naomi Novik’s recent Spinning Silver. It just blew me away; I enjoyed it much more than Uprooted. There isn’t all that much I can tell you without spoiling, but i really like the way Novik both tears down and upholds fairy tale conventions.

In medieval times, the Miller was seen as an untrustworthy or dishonest character, ala the Miller in Chaucer. According to Dr. Darcy Armstrong, whose wonderful lecture series on the Middle ages I am currently listening to on Audible, the portion of grain a Miller would keep was called the “soke”, and it was very easy to keep his finger on the scales and get more than he was due. Apparently, this is the origin of the phrase “to get soked”. Given the Miller in this story basically screws his daughter, his grandkid, Rumpelstiltskin, and then gets off scot free, I’d say hes living up to the stereotype of the times.

Marie wrote:

But it is the miller himself who “spins” (turning of millstones) wheat into gold (payment for services rendered). However, his daughter can apparently take the waste from the wheat harvesting process—straw—and spin it into gold (on a spinning wheel and/or grasped spindle).

This is on my list of “How would Disney expand this into an animated feature?” along with Red Riding Hood.

The English version of this fairy tale is Tom Tit Tot, who’s a little black imp. (Joseph Jacobs collected it.) The name is discovered when the king overhears him bragging:

Nimmy nimmy not! My name’s Tom Tit Tot!

In The Silver Curlew by Eleanor Farjeon, my favorite version of this story, the imp simply implodes from the fury of being outwitted. It is not the idiot king who discovers the name of the imp, but is instead the queen’s (much brighter) younger sister.

As usual, I’m partial to Patricia C. Wrede’s version of this story. Searching for Dragons features Rumplestilkskin’s grandson, who was required to take up the family business of spinning gold for women in this predicament and letting them learn his name so they kept the baby and he got the gold. But unfortunately for him, the women he spun for couldn’t guess his name and he kept ending up with babies he didn’t want but needed to raise — and raise properly, as befitting “long-lost heirs.” He could only support them by spinning gold for more women — “the spell” wouldn’t let him spin for himself or his children — and thus getting more babies. He changed his name to a more-guessable Herman and moved with the children to a remote area, but people still kept finding them and failing to guess his name. Luckily, the book’s heroes figure out a solution to this.

Rumpelstiltskin is no doubt part of the inspiration for Superman‘s Mr. Mxyzptlk (originally Mxyztplk before 1958), a 5th-dimensional trickster imp with effectively magical powers, who periodically shows up to play nasty pranks on Superman or Earth, but is forced to return to his dimension if he can be tricked into saying (or writing or otherwise rendering) his own name backwards.

@14, Poor Herman! Has it occurred to him that the girls aren’t stupid, they’d just rather have the gold?

Ramsey Snow (GoT or SoIaF) could be another incarnation of Rumpelstiltskin.

With the background in @8 and @110, my theory is that the Miller was being called on the carpet by the King to explain his excessive wealth: just how much are you skimming off the taxes that are supposed to be passed on to me? And his answer is, “No, your Majesty, of course I’m not stealing from you! All that gold comes from my daughter!”

For a slightly different take…

Warning – that comic is fine, but a lot of what that artist does is most def NSFW.

The take on this story that I had read is that Rumplestiltskin was casual (and vulgar?) terminology for “foreskin” and a term unlikely to pass the lips of a queen. This would have been all the more reason she wouldn’t have been expected to guess it.

@20/NGneer: I don’t know where you read that, but “rumpeln” is German for “to rumble”, and “-chen” (“-kin” in the English version) is a diminutive suffix. The name suggests that he’s a kind of poltergeist. The queen didn’t guess his name because it isn’t an actual name – there was no chance that she could have heard it before.

@13 “Tom Tit Tot” was delightfully retold by Susanna Clarke in The Ladies of Grace Adieu, from the girl’s point of view. But my favorite modern Rumpelstiltskin is by Jonathan Carroll, in one of his best books (this is a spoiler, look away if you don’t want it)…

… Sleeping in Flame. It’s from the baby’s point of view, after it grows up! Rather metatextual, with a passage of historical discussion actually stolen from Jack Zipes, if I remember correctly.

The lovecraftian version of this story at the beginning of Laird Barron’s The Croning is great.